Romain Moïka and Clément Schoevaërt here engage in a collaborative artistic intervention in the Belleville neighbourhood of Paris, around Rue Lemon and Rue Denoyez. These streets are renowned for their vibrant street art scene and have historically been spaces of cultural expression and community engagement.

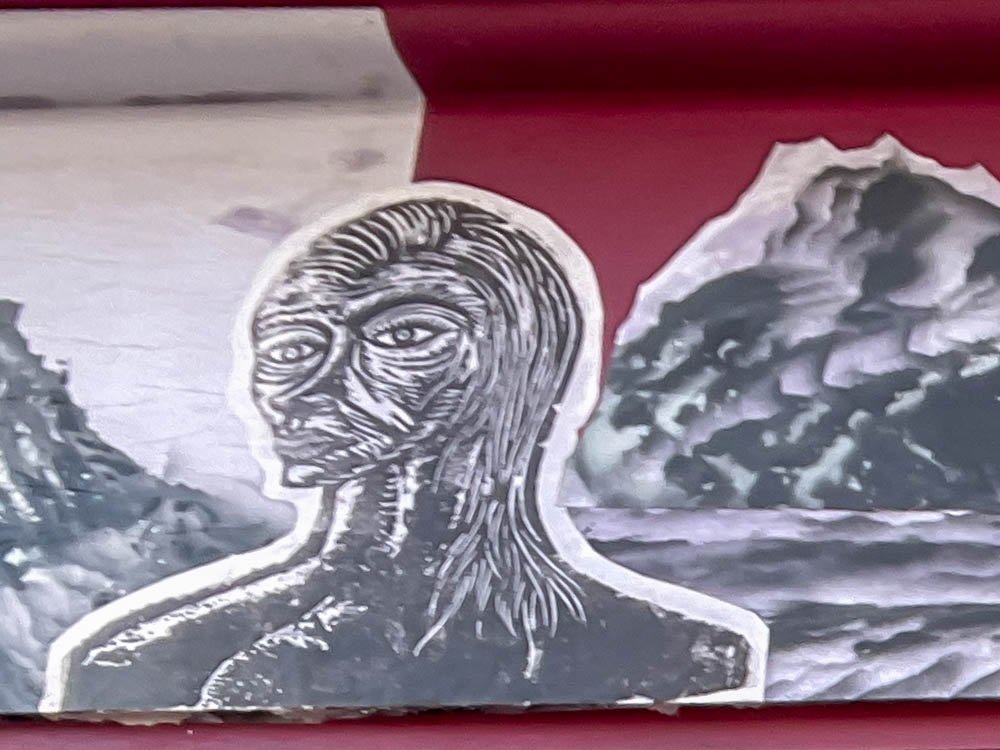

Romain Moïka is a French multidisciplinary artist whose practice delves into the interplay between material fragility and emotional resonance. Her work often interrogates perception and emotion, pushing the boundaries of image and form until they verge on abstraction.

To consider Belleville today is to confront a paradox of presence and absence: a neighbourhood alive with memory, creativity, and struggle, yet simultaneously under siege by forces intent on its erasure. The brush that passes from hand to hand here is no mere instrument of artistic expression. It is a tool of survival, a marker of collective life in a city eager to expunge those who do not fit its sanitised vision.

Art in Belleville is not an isolated object, hung in a frame or displayed behind glass. It is an act of resistance inscribed directly onto the surfaces of the lived environment. It insists that the streets themselves are sites of creativity and community. And here the meaning of “community” must be understood not as a nostalgic ideal but as a lived condition: a space where children of varied backgrounds come together, where social divides are negotiated and contested through play, through shared labour, and through the simple act of being seen.

The vultures circling over Belleville are no distant metaphor. They represent the economic and cultural logics of gentrification, extraction, and displacement. These forces do not merely consume a neighbourhood’s material assets; they harvest its future by displacing those who sustain its life. The “eggs in the nest” — the young, the creative, the working-class families — are taken, their potential commodified or extinguished.

Yet resistance does not only take the form of opposition. It also takes shape as transformation. Through sustained interaction in the public spaces where children play and communities gather, the predator—the vulture—is not static. It changes. Adaptation occurs in the shared spaces of life and struggle; it is a mutation born of the refusal to be erased.

This transformation is neither romantic nor inevitable. It is the product of years of conflict, of systematic engagement across class and cultural lines. It is embodied in the acts of those who insist on inhabiting the city not as consumers or subjects but as creators and citizens. The brush, therefore, is more than a symbol: it is a practice of communal self-making, a refusal written in colour and form against the slow violence of displacement.

What stops the vulture is not sentiment, nor performative gestures of inclusion. It is the construction of an architecture of refusal — legal protections, collective ownership, cultural land trusts, rent regulation, and, crucially, the assertion of a community’s right to define its own cultural value. This refusal is infrastructural and symbolic; it reclaims not only space but the power to narrate the city’s identity.

Belleville’s struggle is a reminder that culture is not a mere accessory to urban life but its foundation. To displace culture is to sever the roots of community itself. What is at stake, then, is not simply who occupies space but who is allowed to imagine, create, and sustain the future.

The nest remains. The brush is still passed. And in that persistence lies a lesson for cities everywhere: the true resistance to extraction is not merely opposition, but the collective, ongoing act of living, making, and refusing to disappear.